Astrological significance

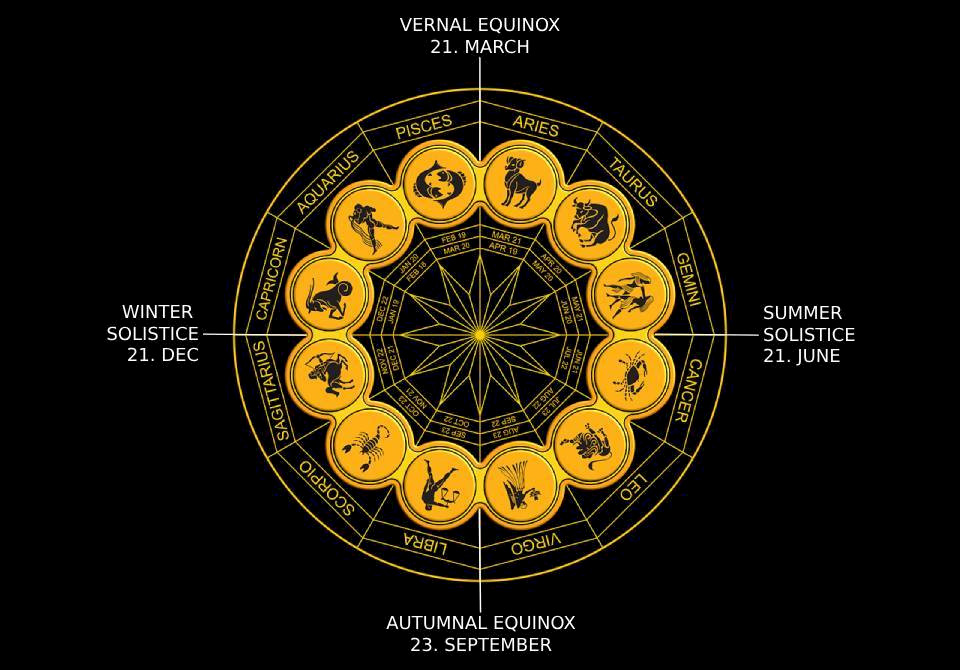

In the tropical zodiac of Western astrology, the summer solstice falls close to the transition into the sign of Cancer, while the winter solstice marks the entry into Capricorn. Both are cardinal points of the annual cycle.

Astrologically, the time of the solstice is therefore often considered a turning point: the summer solstice symbolically marks the beginning of the phase of maturity and retreat of the sun (and of life), which lasts until the autumn equinox, while the winter solstice heralds the new beginning of the solar year.

In other astrological systems, the 24 Chinese seasons (“Jieqi”) also play a role: there, the summer solstice is called Xiàzhì and the winter solstice Dōngzhì.

Spiritual perspectives

In many nature religions and esoteric traditions, the solstices are celebrated as times of great spiritual power and renewal. They are central festivals in the annual cycle of neopagan movements: for example, the solstice festivals in Wicca are called “Litha” (summer) and “Jul/Yule” (winter).

The summer solstice is often associated with fertility, renewal, and the triumph of light over darkness. In many Celtic-Germanic traditions, fire rituals, dancing, and sweat lodges symbolize the expulsion of shadows and the request for a rich harvest.

The winter solstice, on the other hand, represents birth and new beginnings—for example, in Germanic paganism, the Yule festival symbolizes the rebirth of the sacrificed god of the year (death of the old year) and the promise of increasing sunlight.

In modern New Age and shamanic practices, there is a similar emphasis on the fact that after the longest night, a new cycle begins and, as the days grow longer, the yang light grows stronger again (the beginning of a time of light).

Historical origins and rituals

• Stonehenge (England): This Neolithic monument (built around 3100 BC) is famously aligned so that the direction of sunrise on the day of the summer solstice coincides with the central trilithon horseshoe. Archaeologists therefore believe that Stonehenge served, among other things, as a prehistoric observatory and place of worship where social or cult rituals took place at the solstices.

• Yule (Germany and Scandinavia): In the Nordic tradition, Yule was celebrated around the winter solstice. Historically, the date was probably in the middle of winter (the longest nights), which merged with the date of Christmas. In pre-Christian times, it was considered a festival celebrating the rebirth of the sun. In neo-paganism, Yule is celebrated as one of the most important festivals of the year, symbolically celebrating the resurrection of the god of the year or the victory of the new king of the year at the winter solstice. The house was consecrated and eating traditions were observed (today, for example, many Christmas customs such as incense burning or Yule logs).

• Inti Raymi (Andes, Peru): The festival of the sun god Inti was the most important annual festival in the Inca Empire and fell on the winter solstice (June 21–24 in the southern hemisphere). The sun was worshipped as the father of all living things and celebrated for “returning” after the shortest night of the year. Even today, Inti Raymi (literally “festival of the sun”) is held in Cusco as a colorful revival of the Inca rituals.

• Dongzhi Festival (China): In East Asia, too, the winter solstice is traditionally an important family and ancestral festival. Historically, the Han rulers performed ceremonies to “congratulate winter,” and to this day, Dongzhi is considered one of the four most important festivals of the year. Traditions such as eating sticky rice balls (Tangyuan) together symbolize the unity of yin and yang and the prospect of increasing light. A Chinese cultural report emphasizes that the Dongzhi Festival “in ancient times ... was a meaningful and important festival.”

Significance in Taoism

In Daoism, the solstices embody the cyclical dynamics of yin and yang. The summer solstice marks the peak of the yang principle: “With the summer solstice, the yang principle reaches the peak of its growth and begins to decline, while the yin principle gradually begins to increase.”

Accordingly, the winter solstice represents the reversal: since the longest night, the yang energies are now increasing again and a new cycle begins (daylight increases). The famous Taiji symbol illustrates this constant change (in Laozi Daodejing 77, it says that what is high pulls down, and what is low lifts up).

For Daoists, it is essential to live in harmony with this cosmic rhythm: health and harmony arise when humans (microcosm) and nature (macrocosm) vibrate in balance with yin and yang. The solstices remind us that every peak is followed by a period of calm and vice versa – a pattern that can be seen in all natural cycles.

Connection to classical Chinese medicine

TCM also derives recommendations for lifestyle and nutrition from the solstices. According to the five-element principle, summer is associated with the fire element (heart/energy, yang time), and winter with the water element (kidney/substance, yin time). In midsummer (yang in abundance), the heat causes body fluids (yin) to decrease and the pores to open.

That is why TCM recommends choosing cooling and liquid-rich foods in summer – but ideally cooked to protect the digestive qi. Ice cream and raw salads cool you down externally, but they easily weaken the spleen/stomach qi and can lead to “digestive collapse” in the long run. Traditionally, summer soups (gazpacho, cooked vegetables, fruit compote) are therefore used and emphasis is placed on easily digestible grains (wheat, millet).

According to Chinese medicine, cold (yin) dominates in winter, which is why you should protect yourself from cooling down and strengthen your body with warming foods. The kidney yin and yang are considered particularly, people tend to enjoy cooked stews, soups, and spices, and increase their intake of warming foods and proteins (meat, legumes). At the same time, they eat nutritious foods that strengthen the kidney substance, such as nuts, dried fruit, legumes, and root vegetables.

Overall, diet and activity should take the seasonal climate into account: heat and humidity in summer (damp heat) are balanced by cooling, lighter foods, while cold and dryness in winter (cold heat) are balanced by warming, nutritious meals.

The aim is to keep the body and mind in balance with the changing yin-yang rhythm of the seasons.

Wolfgang Heuhsen 2025